In This Issue:

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”Quotes of the Week” no=”1/1″]

“I’ve long suspected that some percentage of the achievement gap in American schools is a time-on-task gap – just time lost to disruption, chaotic classrooms, interruptions, etc.”

Robert Pondiscio in an interview with Matt Barnum in Chalkbeat, October 16, 2019,

https://bit.ly/31sKUqA

“There’s a fine line between being a leader and being a boss.”

A Connecticut teacher (quoted in item #9)

“Teaching is a taxing profession… In urban settings like mine, many schools churn through a quarter or more of their teachers annually, and roughly half of teachers leave within five years.”

Henry Seton (see item #1)

“Tweens may think bad feelings stick around forever, struggle to interpret feedback, or have no idea how to make themselves feel better.”

Phyllis Fagell (see item #3)

“Solicit their opinions, treat them as the expert in their lives, and speak above their maturity level to convey respect.”

Phyllis Fagell (ibid.)

“[Taking care of each other means] saying hi to someone lonely. Giving compliments when we can. Being kind when it is a stretch. Never excluding. Risking a little of our own selves to take care of each other.”

Amber Chandler (see item #4)

[/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”1. Educators Open Up About Their Own Mental Health Issues

” no=”1/1″]

(Originally titled “The Elephant in the Classroom”)

“Teaching is a taxing profession,” says veteran high-school teacher Henry Seton in this article in Educational Leadership. Teachers are asked to watch for signs of anxiety, bullying, trauma, and depression in their students, but they may not be paying enough attention to their own mental health. “In urban settings like mine,” he says, “many schools churn through a quarter or more of their teachers annually, and roughly half of teachers leave within five years.” Among idealistic young educators, some of this is self-inflicted: “We became locked in competition with one another to see who arrived earliest, stayed latest, and showed up for the most weekend sports events… We maybe even secretly took pride that we weren’t the colleague regularly in tears in the staff room. We became numb to other people’s stress.”

In the schools where he’s worked, Seton has noticed that it was okay to talk about certain ways of coping with stress and burnout – yoga, spin classes, caffeine, alcohol – but not therapy, which seemed like “an awkward overshare,” a sign of weakness, of not being sufficiently organized and disciplined. When he experienced signs of burnout, he started seeing a therapist – but he didn’t tell colleagues.

Then in May 2017 Seton and his wife lost their baby a month before her due date, leaving them “utterly flattened, traumatized, and incapacitated. We quickly realized we were walking textbooks on the classic signs of depression: anxiety, guilt, sleeping and eating problems, and lack of energy and interest in life.” Seton made it through the school year and then things got worse: panic attacks while driving, uncontrollable hyperventilating at night. He had no choice but to start anti-depressant medication and engage in grief counseling, cognitive behavioral therapy, adaptive thinking, and meditation.

When the next school year began, Seton talked openly about his treatment. Colleagues opened up about their own mental health struggles, and he steered them toward appropriate resources. They may not have experienced an event as devastating as his family’s, but the daily work of absorbing the stresses and trauma of their students – stabbings, shootings, sexual assaults, fires, deportations – created acute secondary trauma. Seton believes school leaders need to step up in several ways:

– Create safe, confidential spaces to process work stress with well-trained facilitators.

– Offer generous benefits to support staff mental health.

– Regularly gather and respond to teacher feedback about existing stress points.

– Model vulnerability and openly discuss mental health issues.

“The Elephant in the Classroom” by Henry Seton in Educational Leadership, October 2019 (Vol. 77, #2, pp. 77-80), available for ASCD members or purchase at https://bit.ly/2N3RGha; Seton can be reached at hseton@gmail.com.

[/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”2. A Middle School Does a Schoolwide Readaloud on Mental Health

” no=”1/1″]

In this article in Literacy Today, Allison Glickman-Rogers and Beth Zirogiannis (principal and director of English at Oceanside Middle School, Long Island, New York) report that one in five young people are personally experiencing, or live with loved ones who are experiencing, mental health issues. Their school decided to address the stigma of mental illness, “a stigma,” they say, “that can isolate students and prevent them from accessing appropriate support.” A work of literature seemed like the best way to start a dialogue on this difficult subject.

Teachers and administrators considered a number of options and chose the novel, The Science of Breakable Things by Tae Keller (Random House Books for Young Readers). The book’s protagonist sets out to “rescue” her mother, who is suffering from depression and having difficulty getting out of bed every day. The school sold copies of the book at back-to-school night and encouraged families to read alongside their children. In November, a schoolwide readaloud began, with departments taking turns reading chapters aloud in class – one in math class, one in science, and so on.

“It was a whole new experience,” said a seventh grader, “knowing everybody around you was listening to and reading the same story.” A math teacher said, “I loved sharing a different side of myself with my students and seeing a different side of them as well.” ELA teachers took the lead on literary aspects of the book, but teachers in other subjects chimed in as well. “The best part about the readaloud,” said one ELA teacher, “was that students had the opportunity to talk to teachers other than me about a book they love.” The culminating event was a visit from the author, who conducted grade-level assemblies, visited classrooms, signed books, and hosted an evening book talk with families.

“It was good to expose middle-school students to the topic of mental illness,” said an eighth grader, “and how it affects everyone involved, not just the person suffering.” Since the schoolwide readaloud, counselors, psychologists, social workers, and administrators report more openness on the subject, as well as more students taking advantage of Sprigeo, a confidential system that allows students to report concerns about peers. Everyone’s big takeaway was that the school was a safe place to discuss what had been a very tricky issue.

Glickman-Rogers and Zirogiannis list four other books they considered for schoolwide discussions of mental health:

– Umbrella Summer by Lisa Graff (HarperCollins)

– Some Kind of Happiness by Claire Legrand (Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers)

– Small As an Elephant by Jennifer Richard Jacobson (Candlewick Press)

– Nest by Esther Ehrlich (Yearling Books)

“Sending a Powerful Message” by Allison Glickman-Rogers and Beth Zirogiannis in Literacy Today, September/October 2019 (Vol. 37, #2, pp. 44-45), https://bit.ly/2P2Tfia; the authors are at aglickman-rogers@oceansideschools.org and bzirogiannis@oceansideschools.org.

[/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”3. Can Teachers Be Amateur Counselors with Their Middle Schoolers?” no=”1/1″]

“Tweens may think bad feelings stick around forever, struggle to interpret feedback, or have no idea how to make themselves feel better,” says Washington, DC school counselor and author Phyllis Fagell in this article in AMLE Magazine. Here’s what an angry 14-year-old at Fagell’s school experienced one day: she took offense when a classmate made an innocuous comment about her weekend plans; she felt rejected when there wasn’t room to sit with her friends at lunch; and when she was scolded by a teacher for being chatty that afternoon, she yelled that she always got blamed for everything and stomped out of the classroom. Sitting with this angry girl a few hours later, it took a while for Fagell to get her to identify why she was so on edge: she’d had a fight with her mother on the way to school.

Eruptions like this happen all the time with young teens, who are seldom in touch with the underlying reason that an argument, a slight, an or an ambiguous comment can sour their mood. Fagell suggests some counseling techniques that any educator can use:

• Artfully reframing – “Getting disinvited from a sleepover, bombing a test, or getting excluded from a gift exchange all can feel like catastrophes,” she says. One trick is helping kids think about the situation as if they were looking down on it from a hot-air balloon. Another approach is walking through it step by step to the logical conclusion: Will it really turn out so badly? And if it does, what will you need to cope?

• Challenging distorted thinking – Students “think in black and white, overgeneralize, and discount the positive,” says Fagell. A boy might ignore numerous positive comments on a presentation and obsess about one snarky remark about his voice cracking. Adults need to point out faulty perceptions and ask kids to come up with alternative possibilities.

• Validating – There’s a tendency to refute comments like, “You never call on me” or “No one ever wants to be my lab partner,” but a better approach is to acknowledge the feeling and sympathize with it: “If I thought no one wanted to be my lab partner, I’d be pretty upset too.” Feeling heard makes it more likely that a student will be open to taking the next step and solving the problem.

• Listening actively and reflectively – Repeating students’ concerns back to them, says Fagell, “requires concentrating, matching a student’s body language, turning toward them, eliminating distractions, making eye contact, and ensuring your tone, gestures, and words are in alignment.” And no shuffling papers or glancing at your computer!

• Providing psychoeducation – Counselors can help other educators in their school understand the difference between depression and normal teenage mood fluctuations, and know when to talk to a student themselves or make a referral to a specialist.

• Scaffolding risk-taking – For example, if a student has been taking tests in a separate room as part of an IEP, see if she can take a test in her regular classroom with her back turned to classmates. If a student is afraid of making a presentation to his class, have him present to a few trusted friends or read from a script.

• Asking open-ended questions – For example, How do you learn best? What excites you? What progress do you hope to make in your class? “Solicit their opinions,” says Fagell, “treat them as the expert in their lives, and speak above their maturity level to convey respect.”

• Linking thoughts to feelings and behaviors – “Tweens experience intense lows and are wired to remember the negative, and that makes middle school the perfect time to reinforce positivity and optimism,” says Fagell. Teachers might have students fill in charts on their mood or hang their names on a clothesline that shows their emotions, then discuss ways to turn around a sour frame of mind – and also savor and extend moments of joy.

“Eight Counseling Techniques Every Middle-School Educator Can Use” by Phyllis Fagell in AMLE Magazine, October 2019 (Vol. 7, #4, pp. 39-41), https://bit.ly/2MAQ8wd

[/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”4. Why Teens Are So Moved by Plays and Films About Suicide” no=”1/1″]

In this article in AMLE Magazine, alternative education coordinator and author Amber Chandler describes watching the play Dear Evan Hansen with her 14-year-old daughter and other teens and their families. Chandler was struck by “heartfelt sobbing” during the show, and links it to teens’ intense interest in dramatic productions involving suicide, including 13 Reasons Why and Heathers. She believes this is a sign of a “profound loneliness in the midst of constant connectedness via screens [and] might be a generation-defining issue.”

Talking about the play the next morning on the way to school, Chandler’s daughter said that kids and adults “just need to take care of each other.” What does this look like in classrooms, schools, and communities? It means “saying hi to someone lonely,” says Chandler. “Giving compliments when we can. Being kind when it is a stretch. Never excluding. Risking a little of our own selves to take care of each other. I’m optimistic that this is a kind of social responsibility that will resonate with middle schoolers: autonomous, specific, and based on the sobs I heard, a need they understand.”

“What Does Social Responsibility Mean to a Middle Schooler?” by Amber Chandler in AMLE Magazine, October 2019 (Vol. 7, #4, p. 38), no e-link available; Chandler can be reached at amberrainchandler@gmail.com.

[/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”5. Dealing Effectively with In-Person and Online Bullying” no=”1/1″]

(Originally titled “Looking at Bullying in Context”)

In this Educational Leadership article, psychologist Elizabeth Englander (Massachusetts Aggression Reduction Center) says that with student-to-student bullying, context is critically important. What might seem like a random, thoughtless act – a student sticking out his tongue at a classmate, a girl saying, “What an ugly sweatshirt” – can be much more serious if there’s more going on, perhaps online. Educators are constantly deciding whether “gateway behaviors” – teasing, eye-rolling, excluding former friends – are no big deal or need to be addressed.

That’s why adults need to go beyond the usual questions – What happened? Where and when? Did it happen in front of others? How serious was it? – and find out if an incident is part of intentional, repeated cruel acts. Repeated bullying is much more likely to produce anxiety, upset, depression, trauma, social rejection, and poor grades.

Online bullying is a little more complicated, since the usual trifecta of bullying – intentional, repeated, by someone more powerful – doesn’t always apply. For example, if a single mean comment on social media is seen by many people, is it repeated? Does anonymity give the bully more power? And if online bullying continues during school hours, does that make it worse? (It usually does.) Englander suggests asking these questions when a student reports cyberbullying by a perpetrator:

– Tell me exactly what he wrote. Did he write anything else?

– On what platform did this happen: messaging, gaming, social media?

– Has anyone else seen the comment?

– Is this the first time he has been mean to you? Has he said or done other things to make you feel bad? What about here at school?

– How upset are you feeling? Is this a big upset or a little upset?

– Are there other kids who make you feel badly here at school or online? Tell me about that.

These questions help put the incident in context and help the adult decide what to do next, including, of course, involving families.

“Looking at Bullying in Context” by Elizabeth Englander in Educational Leadership, October 2019 (Vol. 77, #2, pp. 54-58), available for ASCD members or for purchase at

https://bit.ly/2qvtw7H

[/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”6. Dyslexia: Myths, Look-Fors, and Classroom Strategies” no=”1/1″]

In this Cult of Pedagogy article, Jennifer Gonzalez confesses that when she was a classroom teacher, she was “woefully ill-equipped to support students in my room with special needs – those who arrived with a formal diagnosis and those who didn’t.” She followed students’ IEPs, which usually involved shortening assignments, giving extra time, and sometimes reading material out loud, but didn’t see those strategies as very helpful.

Of course every school has trained special educators, but since they have limited time and many students with IEPs are spending an increasing amount of time in regular-education classes, Gonzalez believes it’s important “for the rest of us to step up our game.”

She believes a good place to start is dyslexia, and interviewed Lisa Brooks of the Commonwealth Learning Center’s Professional Training Institute in Massachusetts. Brooks started with two common misconceptions:

• Myth #1: Dyslexia is uncommon. In fact, experts believe 15-20 percent of students are affected to some degree, which means in a class of 20 students, three might have some symptoms. Missing a dyslexia diagnosis – perhaps saying a student has attention problems or is developmentally immature – can delay important interventions.

• Myth #2: Dyslexia means the child reads or writes backwards. It’s actually common for children up to age six to write letters backwards. This isn’t what dyslexia is about, says Brooks: “It’s really a difficulty in the phonological component of language, and that means children having difficulty with the sounds of words.”

So what symptoms of dyslexia should teachers look for? Two are particularly important to spot in the primary grades, and dealing with them early can make a big difference in students’ future success:

• First, a student’s struggles in reading and writing are unexpected because he or she is strong in other areas. If a child has a good vocabulary, speaks in paragraphs, and loves books but has trouble remembering a letter or a letter sound, that’s a clue.

• Second, the student has difficulty with the sounds of language – for example, identifying the first letter when sounding out a word; blending sounds into words; segmenting words into sounds; pronouncing multisyllabic words like specific; rhyming; performing rote memory tasks like remembering songs or the days of the week; correctly repeating words; or spelling a word without representing all its sounds (for example, writing butterfly burfly).

Gonzalez and Brooks suggest several effective strategies to support students with dyslexia:

– Direct instruction in phonics, teaching students to crack the code of language.

– Overlearning – these students need a lot more practice with skills than other students do, even if it seems boring.

– Learning experiences that involve using more than one sense simultaneously – for example, naming a word, tracing the letters, segmenting it, and writing it.

– Sound, music, and rhyming games – these are fun ways to give students more practice.

“How to Spot Dyslexia, and What to Do Next” by Jennifer Gonzalez and Lisa Brooks in Cult of Pedagogy, October 13, 2019, https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/spot-dyslexia/

[/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”7. Questions That Help PLCs Close Achievement Gaps” no=”1/1″]

In this article in The Learning Professional, Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey (San Diego State University and Health Sciences High) and John Almarode (James Madison University) say professional learning communities are not always fulfilling their potential. The authors suggest five questions to focus same-grade/same-subject teams on improving teaching and learning and achieving equitable outcomes:

• Where are we going? Learning goals that are well-framed and clear can also contain low expectations – for example, a fifth-grade team planning lessons based on third-grade expectations. When this happens, say Fisher, Frey, and Almarode, students don’t work up to their potential and achievement gaps aren’t closed. Teacher teams need to put grade-level expectations on the table, analyze the gaps and barriers to better performance, and orchestrate the support that students need.

• Where are we now? “When teams discuss the current performance levels of their students,” say the authors, “they are often confronted with the reality that some students have not had equitable opportunities to learn to grade-level standards, and they are called on to accept responsibility to close the gap.” This is the heart of PLC work.

• How do we move learning forward? When teams don’t get specific on this question, say Fisher, Frey, and Almarode, “some well-meaning teachers end up using ineffective approaches, like assigning worksheets or doing all the work for students.” The culture of a teacher team has to be such that team members are candid with each other and share teaching practices that produce results – including materials and pedagogy that are culturally relevant.

• What did we learn today? This includes students’ academic progress based on frequent checks for understanding, and also teachers’ lesson-by-lesson insights on what’s working, what reteaching and extension tasks are necessary, and how pedagogy can be improved.

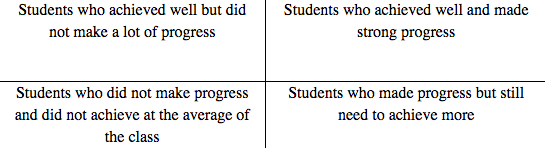

• Who benefited and who did not? The authors believe it’s important for PLCs to break down assessment data by student subgroups. The Progress versus Achievement Tool is helpful www.visiblelearningplus.com/groups/progress-vs-achievement-tool (registration required). So is plotting students’ achievement on this quadrant:

One teacher team that used this approach noticed that the lower left-hand quadrant was filled with English learners. “Without visualizing the data this way,” said a teacher, “I would have focused on the individual students in my class who needed more support. But it’s clear that we need to do something different for our English learners if we have any hopes that they will succeed.”

“5 Questions PLCs Should Ask to Promote Equity” by Douglas Fisher, Nancy Frey, and John Almarode in The Learning Professional, October 2019 (Vol. 40, #5, pp. 44-47),

https://bit.ly/2pDNI6W and scroll down; the authors can be reached at dfisher@sdsu.edu, nfrey@sdsu.edu, and almarojt@jmu.edu.

[/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”8. Using a Voicemail App to Run Cross-District Book Discussions” no=”1/1″]

In this article in The Learning Professional, Illinois district leaders Erin Axelsen, Lorie Cristofaro, and Jill Geocaris describe how an app made it possible for them to use commuting or exercise time to take part in book studies with several colleagues. Voxer is a free mobile app that allows people to leave voice messages with other members of a group, and it notifies members when someone chimes in. Recipients have the choice of clicking on the message and listening to it live (as if on a walkie-talkie) and joining the discussion, or waiting until later to click on it and participate.

Axelsen, Cristofaro, and Geocaris say there’s no way that interested educators in different districts could have managed live, in-person book discussions, but using the app came pretty close. “Voxer allowed us to hold a discussion at times that are convenient for each individual,” they say, “yet still facilitate a conversation that builds on one another’s ideas.”

The authors, who had been involved in coaching pairs the previous year, recruited a number of colleagues and organized them into groups of five or six. Each group appointed a facilitator, decided on a book, set up a chapter schedule, and established a few norms, including confidentiality so people would feel free to speak candidly. Discussions often began with one person citing a quote or idea from the assigned chapter that was particularly striking, then others chimed in with reactions, new ideas, or questions.

A big advantage of this asynchronous dynamic, say Axelsen, Cristofaro, and Geocaris, “is that participants don’t need to wait for an upcoming meeting to share an idea. As you read the book and something comes to mind, you can quickly grab your phone and share your idea or ask your question immediately.” When some participants are too busy to take part, the facilitator can jump in and move the discussion forward.

One interesting feature of the free version of Voxer is that voice messages can’t be edited or deleted (for a fee, this feature can be added). Not being able to make deletions makes discussions more like an actual conversational stream of consciousness, leading members to adopt the kind of etiquette a group would use in a face-to-face discussion.

“Your Voice Mailbox Is Full – of Learning” by Erin Axelsen, Lorie Cristofaro, and Jill Geocaris in The Learning Professional, October 2019 (Vol. 40, #5, pp. 36-38),

https://bit.ly/2pDNI6W and scroll down; the authors can be reached at erin.axelsen@cusd200.org, lcristofaro@lths.org, and jgeocaris@maine207.org.

[/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”9. Principals’ and Teachers’ Differing Responses to the Same Questions” no=”1/1″]

This article in Education Week reports on a survey comparing teachers’ and principals’ perceptions on a number of schoolhouse issues [the wording of some questions has been slightly edited]:

· Is it very important for teachers to have a positive working relationship with the principal?

– Principals: 87% agree

– Teachers: 81% agree

· Do teachers in your school feel empowered to bring problems to the principal?

– Principals: 69% completely agree

– Teachers: 25% completely agree

· Does the principal support teachers who start innovative work or new initiatives?

– Principals: 86% completely agree

– Teachers: 45% completely agree

· Rate the principal’s contribution to the school’s working and learning environment:

– Principals: 77% completely positive

– Teachers: 37% completely positive

· Frequency of the principal’s formal and informal feedback to teachers on instruction:

– Principals: 2% daily, 23% weekly, 29% monthly, 46% a few times a year

– Teachers:, 2% daily, 5% weekly, 10% monthly, 71% a few times a year, 13% never

· In teacher-principal relationships in your school, which is a major source of friction?

Student discipline:

– Teachers: 52% say it is

– Principals: 24% say it is

Scheduling, the timing of planning periods:

– Teachers: 24%

– Principals: 14%

Non-teaching assignments (e.g., lunch and hall duty):

– Teachers: 21%

– Principals: 14%

Instructional approach, philosophy:

– Teachers: 21%

– Principals: 9%

Parents:

– Teachers: 19%

– Principals: 11%

Principal feedback on teaching:

– Teachers: 17%

– Principals: 5%

Professional development requirements and opportunities:

– Teachers: 16%

– Principals: 8%

Class and subject assignments:

– Teachers: 14%

– Principals: 5%

A few quotes from the survey:

– A Texas principal: “That’s been the biggest frustration in the districts I have been at, teachers have questioned the consequences that a student received, that they weren’t harsh enough.”

– A Colorado principal: “All too often, principals are in classrooms… taking copious notes… They rattle off all the notes… and it doesn’t help the teacher improve anything.”

– A South Carolina teacher: “Using evaluation tools as punitive assessments really doesn’t do anybody any good.”

– A Connecticut teacher: “There’s a fine line between being a leader and being a boss.”

“Principals, Here’s How Teachers View You” in Education Week, October 15, 2019 (Vol. 39, #6, pp. 4-5), https://bit.ly/33L3MCS

[/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”10. A Principal Keeps the Fire Burning Bright” no=”1/1″]

In this article in The Learning Professional, veteran Massachusetts principal Ayesha Farag says, “I’ve had a growing awareness of how my expectations for myself and the urgency I feel to act quickly exacerbate the stresses inherent in the role.” She’s adopted three practices that are helping her keep the “passion, energy, and enthusiasm that fuel the important work of leadership:”

• Connect with other school leaders. She gets a lot of ideas and support from the 14 fellow elementary principals in her district, as well as leaders she meets through professional organizations and online.

• Deliberately seek joy. One of the best ways, says Farag, is connecting with students in classrooms and during recess and lunchtime.

• Invest in out-of-school relationships and interests. “Self-care is most important during challenging times,” she says. This year, Farag has committed to a monthly gathering of close friends, and makes a point of showing up even when work gets intense.

“How School Leaders Manage Stress and Stay Focused: Balance Urgency with Purposeful Action” by Ayesha Farag in The Learning Professional, October 2019 (Vol. 40, #5, p. 25), https://bit.ly/2MYujWf; Farag can be reached at ayesha_farag@newton.k12.ma.us.

[/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

[blank_space height=’3em’]

[thrive_link color=’red’ link=’https://tpc-dashboard.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/Marshall+Memo/Marshall-Memo-808.doc’ target=’_self’ size=’medium’ align=”]Download Marshall Memo[/thrive_link]

© Copyright 2019 Marshall Memo LLC